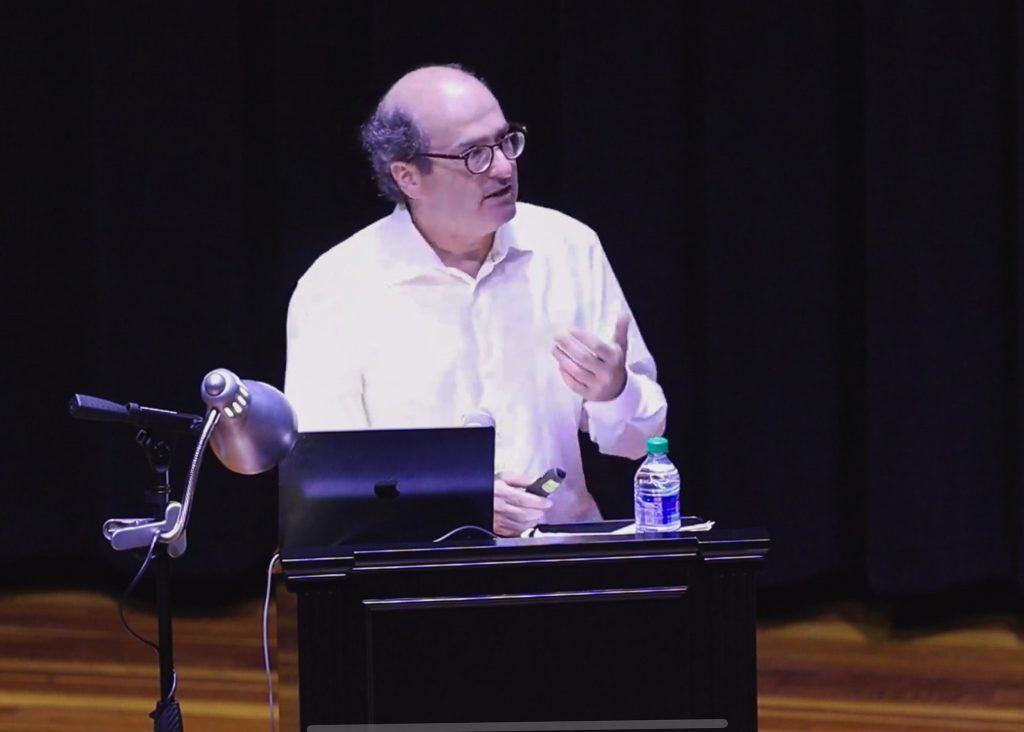

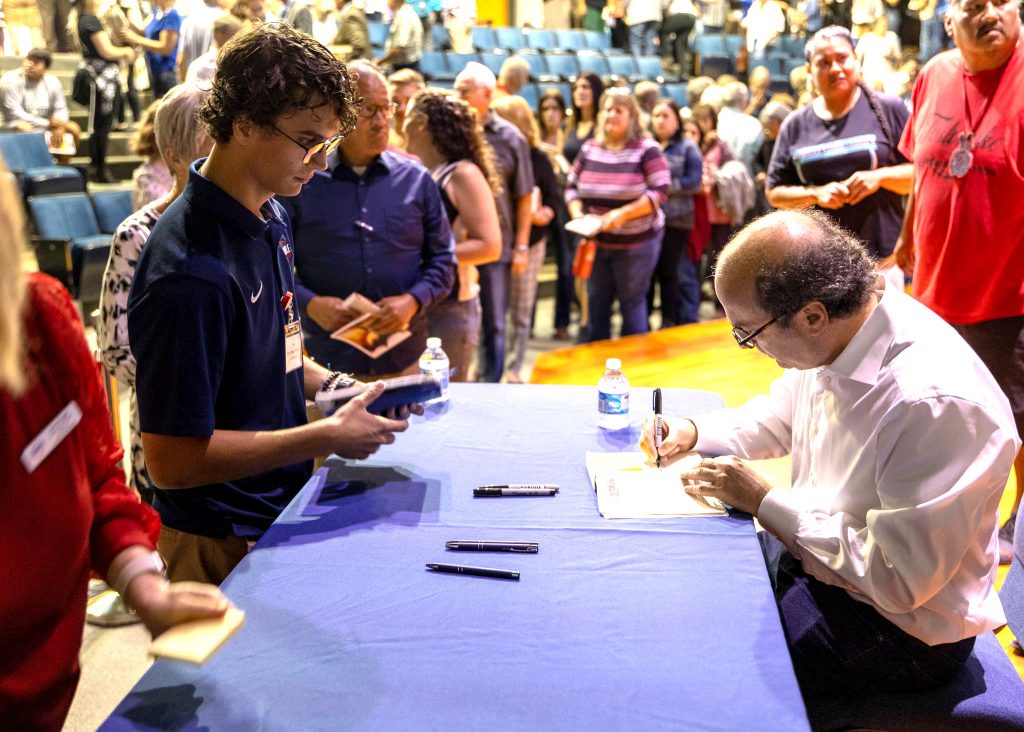

“Killers of the Flower Moon” author David Grann presented his research and writing process to a capacity crowd inside Seminole State College’s Jeff Johnston Auditorium on Sept. 21. The event was sponsored by the Native American Serving Non-Tribal Institutions federal grant program. Students, employees, tribal leaders and community members listened as the writer spoke about the journey of crafting the book, which began with a tip from a historian friend about the Osage Nation Museum.

While touring the museum in Pawhuska, a chance encounter altered the course of Grann’s life, steering him toward the narrative that would later become his nonfiction novel “Killers of the Flower Moon.” It was a pivotal moment, the kind that storytellers and journalists often dream of—a moment when the veil was lifted, revealing a glimpse at a history so shocking that it demanded to be brought to light.

While taking in the museum’s photography collection, Grann fixated on a large panoramic photograph. The photograph, taken in 1924, captured a group of Osage members standing alongside white settlers.

“It looked very innocent,” Grann said. But then he noticed a portion of the photograph was missing. He asked then-Director of the Osage History Museum Kathryn Red Corn what had happened to the missing piece.

“She said it contained a figure so frightening that she decided to remove it. She pointed to the missing panel—and I’ll never forget her voice—she said, ‘The devil was standing right there.’”

The devil, in question, was William Hale, a white cattle rancher who had amassed a fortune through insurance fraud and unfair trade with the Osage. He had deep political connections, and, in 1921, he conspired with his nephews, Ernest and Bryan Burkhart to murder several Osage people for their oil headrights.

At the time, The Osage Nation sat atop one of the largest oil deposits in the country. Under tribal law, each member received a headright, or a share of the mineral trust. In the early 1920s, the Osage were the wealthiest group of people in the country per capita, but members of the tribe were often deemed “incompetent” by the government and forced to enter guardianships, where their own money was controlled by their white neighbors.

Newspapers at the time called the string of unsolved Osage murders the Reign of Terror. Upwards of 60 full-blood Osage members were reported killed from 1918 to 1931, with many historians believing the number to be much higher, given the misreporting and coverups that occurred.

“At the beginning of the process, the question for me wasn’t, should I write this book? The only question was, could I write this book?” Grann said.

The writer recognized that crafting the story required a substantial foundation of underlying materials, oral histories and documents. So, he embarked on a five-year-long journey, tirelessly collecting every fragment of evidence and insight he could find. Freedom of Information Act requests, tribal records, court records, Department of Interior records, prison records, correspondence and establishing connections with descendants were all part of the process.

One of the most daunting obstacles Grann encountered was that the scale of the tragedy was met with deliberate obscurity—records were neglected, hidden or never documented. In these cases of suspicious deaths, the victims had long since passed away, but so had the suspects, eyewitnesses, and even proper investigations.

Gaps in historical documentation underscored the vital importance of interviewing the descendants of those who had endured the Osage murders. Grann recognized that without their firsthand accounts and oral histories, the full scope of the story would remain incomplete.

“The descendants of both the murderers and the victims, many of whom still live in the same neighborhoods side by side, talking to them really drove home to me how recent these killings were. You see how these crimes just devastated the families, how this history still reverberates today,” Grann said.

With the imminent release of the film adaptation of “Killers of the Flower Moon,” directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro and Lily Gladstone, Grann is grateful that this often-overlooked aspect of history will be shared with a broader audience.

“What I hope will happen is that more and more people will learn about this history. The movie, the book, all these things should just be beginnings of conversations,” Grann said.

When asked if the upcoming film had any changes on his personal life, Grann responded, “For at least two days, my kids thought I was cool. If you have teenage children, that’s pretty good.”

Since the book’s release, Grann has made many return trips to Oklahoma for speaking events and to catch up with friends. He admires how vibrant and thriving the Osage Nation is today despite the cruelty the tribe has endured and the efforts to erase important parts of their history.

“You can’t fully erase history. It is always there. It’s up to us to decide how we want the past to shape us. We all need to be historians, to be inquisitive. We all need to learn from our past, both personally and nationally, to become the people we want to be in the future.”